Since 1967, large parts of the Palestinian West Bank are under Israeli control. Why do Israelis settle there – and what does life feel like in this land of discord?

A handful of failed peace processes have left a mark on the last twenty years of Israel and Palestine history. Since the Oslo agreements of 1995, 60 percent of the West Bank has come under full Israeli control. Far from preventing the construction of new Jewish communities in the West Bank, the State of Israel continues to support its citizens to settle in the Palestinian territories. Now, about 380.000 Israeli settlers live in 137 communities in the West Bank. They’ve come from all over the world with diverse life experiences and expectations – and decided to stay. Many blame the settlers for being the major obstacle to the realization of peace in the Middle East.

Rachel, a non-religious young woman, lives alone in her house in Tekoa Dalet. She has studied psychology and is currently working on theater projects with Palestinian and Israeli children.

Not only Israeli troops establish control over the occupied regions of the West Bank. There are further mechanisms to secure the Israeli settlements: First, the building of a huge infrastructure, making life in the settlements more comfortable: water and electricity supplies, roads in and out of the colonies, tunnels, security perimeters around the settlements and checkpoints. Secondly, an organized system of civil institutions such as education and health services, as well as financial benefits for the settlers. Last but not least, the Israeli government’s ideological support of those Jewish citizens who claim Judea and Samaria – biblical name for West Bank – as their Promised Land and therefore fell entitled to settlea anywhere in the territory. “It’s important that the Jewish people have the moral and religious right to remain connected to their roots”, says Dani Dayan. Until 2013, the Argentinian-born political leader and secular man served as director of the Yesha Council – the umbrella organization of settlements in the West Bank.

Although a number of settlers fit the stereotype, only about a third live in a settlement because of ideological motivations: They believe the region to be the heartland of the Jewish people. Another third represent ultra-orthodox Jews who choose to live in settlements because – besides being cheaper – the small communities provide them with more intense religious communal lives. The third group is made up of secular settlers who live in the settlements for essentially economic reasons. They are not necessarily interested in politics and would often prefer to live inside the legal borders of Israel if they could afford it.

Area under construction in the settlement of Nokdim. Through legitimization by the State of Israel, it is possible to built stone houses in a settlement.

Hedged Kindergarden caravan in Nokdim’s trailer park area.

Backyard inside the trailer park of Nokdim. The trailer park area forms a temporary community inside of Nokdim.

Construction in progress of the security system in Nokdim. As new areas of the settlements develop, new walls and fences around are built simultaneously.

View of Tekoa Dalet outpost from the settlement of Nokdim. The settlements are growing in size and as a result frustrating the creation and development of a Palestinian State.

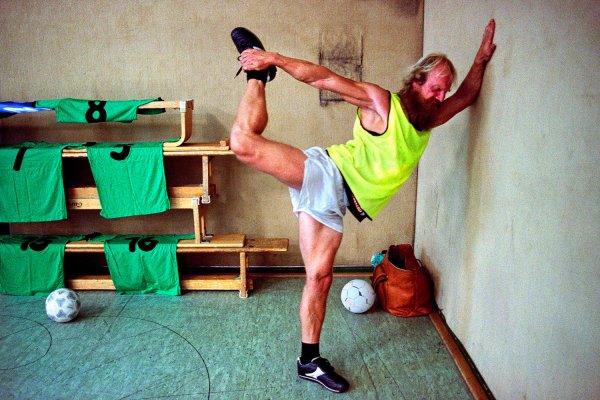

Nokdim is one of many settlements: a rare oasis of limestone homes, red tile roofs and private gardens at the gate of the Judean desert. Among this community of about 1.500 settlers, twenty families enjoy an inexpensive way of life inside the community. Yosef Frenkel, a student of Chinese medicine and a barista in Jerusalem, lives in a trailer. He and Gilat, his wife, are expecting their first daughter. Yosef’s father, Baruch Frenkel, knows the story from the beginning though: He is one of the 290.000 Jews who fled Soviet anti-Semitism in the 1970s. Baruch came to Jerusalem with his wife and his daughter in 1974. Four years later an Israeli guard was killed by Palestinian teenagers near Herodion and Baruch decided to settle in the place where the murder was committed: “It was a blow below the belt in a tense moment after the war, so I joined some men to make a protest”, he says. The expedition didn’t last long, but Baruch kept going to the area and started working as a watchman. “I wanted to build a new village, a new home in Israel”, he explains, “Founding a community was the most important thing for me. First I thought the place isn’t important, but finally I understood. My home had to be built in Judea and Samaria”.They had no water, no public transport, no roads. They got everything from the Israeli army, even shared a phone line with the soldiers for a while. After building up some tents, five families came from Israel and stayed. Like Frenkel, many pioneer settlers believe that building their houses along the West Bank will prevent a two-state solution with the Palestinians. “If someday this place becomes an Arab state, I swear I’ll stand on my roof and protect this land with a Kalashnikov”, declares Frenkel, concealing a smile. Today the Frenkel family consist of three generations of settlers, two of them have never experienced pre-occupation reality. The West Bank is their home.

Military patrol in outpost of Maale Rehavam. Despite being illegal even under Israeli legislation, this outpost is protected by the Israeli army.

Demolished shack in Maale Rehavam.The Israeli authorities have pulled down several buildings as the settlers have built their homes without licenses.The outpost is, according to its residents, about to be linked to the nearby settlement Kfar Eldad, thus legalized.

Nokdim serves as a “parental community” to surrounding outposts like Maale Rehavam. Here, the Bergara Reyes family lives and own several outpost trailers. They made Aliyah – the immigration of Jews from the Diaspora to the Land of Israel – from Peru. Bezalel Bergara was the first from his family to arrive in Israel. He received ‘Sal Klita’, a financial grant handed out by the Israeli government to help Jewish immigrants settle in Israel. Even then he couldn’t afford life in Israel, so he moved into the West Bank allured by the low cost of living. Divorced and without knowing Hebrew, Bezalel was rejected in a couple of settlements: “They condemned my lifestyle because I was alone. Maale Rehavam was the first place that welcomed me”. The shabby and ghostly outpost on top of a desert hill was built 14 years ago, during the Intifada. Since then many neighbours have been evicted from their houses and many caravans have been demolished, as according to Israeli legislation the outpost is illegal. Home demolitions and evictions of settlers are part of the game played by Israel in an attempt to demonstrate adjustment to International Law. Nevertheless, the community of Maale Rehavam has access to water and electricity and enjoys the permanent protection of the Israeli Army. There appears to be a huge grey area between legal and illegal. “We’ve just had a meeting with the mayor in Nokdim and this place is about to be linked and legalized. We’re really happy”, announces Bergara.

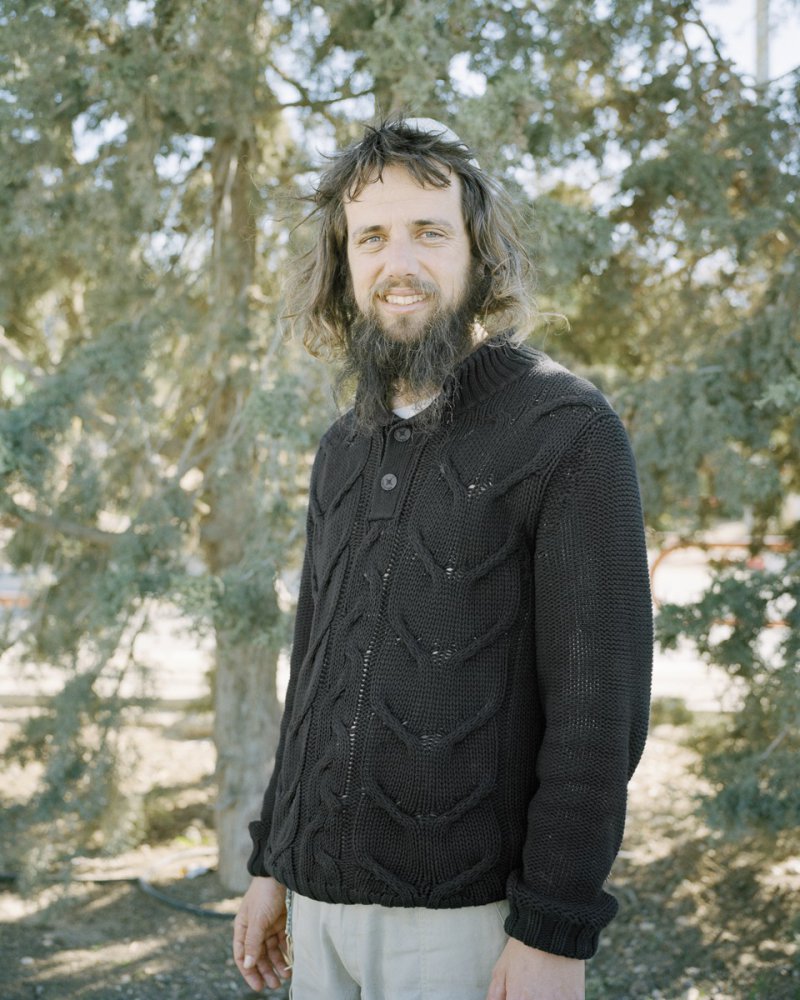

Nachman Gutman used to live in Jerusalem as an ultraorthodox jew. Now, after leaving aside the haredi rules, he runs his own goat dairy in the Sde Bar outpost, where he is also building his caravan with the help of neighboring Palestinians.

Shimon with his wife and youngest son. Shimon came to Israel from the United States when he was 15 and now lives in theTekoa Dalet outpost. His wife Shira has con- verted an old bus into her bridal gown design studio.

Tekoa Dalet settler tries to catch a ride. Hitchhiking is a popular way for settlers to move between outposts, around the West Bank and to travel to the big cities in Israel.

Nachman Gutman, 28, quit ultra-orthodox tradition and moved away from Jerusalem four years ago. In Sde Bar, a small settlement near Nokdim, he opened his business in 2012: an organic sheep and goat farm. With his restaurant looking over the Judean desert, he now tries to make his way into the tourism industry of the West Bank. Currently he employs five Palestinians from the neighboring village who are helping him build his new home, a construction trailer on concrete pillars. “They come here from time to time and help out. We enjoy the time together! That’s one of the reasons why I feel free and safe here”. Palestinians are allowed to work inside the settlements if they are in possession of a Green Card working permit. Brick by brick, they build houses for the settlers.

The security standards, set by the army, have established a segregation system which many settlers help to keep alive.

Elisha, 30, is building his house in the settlement of Tekoa. Together with Chaj Ibrahim, his Palestinian building engineer, he plans another couple of projects in Jerusalem. Elisha always carries a weapon inside his back pocket: “We are forced to keep an eye on the Palestinian workers. I used to carry an M-16. After a while I began to trust Ibrahim, so it felt awkward and I’m now just carrying a small pistol”, he says. “I have to”, he adds.

Right behind the big residential area where Elisha lives, a narrow dirt road leads through Tekoa B to the neighboring hilltop outpost Tekoa C, where Yonatan lives and works. Every tuesday he drives his old red Volkswagen along this road carrying fresh food from the Mahane Yehuda market in Jerusalem. He married four years ago after building his house in the outpost, and has three kids now.

Gilat Frenkel lives with her husband in a trailer park in the settlement of Nokdim. She drives to Jerusalem every day, where she works in an arts and crafts shop.

He learned to cook from his father and now tries to make a living of it. In the kitchen, Yonatan prepares special food for Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest, and receives orders from all over the region. He believes Tekoa is a special community among the settlements. “This place is a beautiful example of Palestinians and Jews living together. We live in the same place, we live from each other.They sell goods we buy, they work here, we do things together”, explains Yonatan with mildness. The harmony he describes feels out of place two kilometers away, where the fence surrounding the colony restricts access to the settlement.

Past Tekoa C, Tekoa Dalet is the last Jewish enclave before the gateway of the Judean Desert. The dunes represent a natural border of the outpost, where settlers raise their families in what they believe to be a peaceful and safe place, where religious and secular people get along. Many declare to have chosen the spot willing to live in a remote place with a beautiful scenery. They live in self-constructed houses, caravans, mobile homes, tents and caves; they grow their food and cultivate olive trees and lemon trees.

Private watchtower in Givot Olam Farm.The outpost, located north of the West Bank and built without a license, has a watchtower that the settlers have built themselves.

Handcrafted house in Tekoa Dalet. Many young settlers and families try to get a spot in the community in spite of long waitinglists.

Young Jew building his house in Tekoa Dalet with the help of several friends. In order to get a residency in Tekoa, one must pass through a lengthy application process in the community.

Community kitchen in the Givot Olam Farm. Above the window, three screens show live images from obvervation cameras.

A voluntary worker in the Givot Olam Farm. Many young people travel there to help out in the outpost during the summer.

The residents of Tekoa Dalet have created an idyllic world in their minds. They overlook the security gates, checkpoints, and spiked barriers as if they were some proper elements of life at liberty.

Israel has taken over the hills of the West Bank. The Israeli settlers, an ordinary crowd, motivated by either religious, ideological or economic reasons, remain heedless and accomplice in the widespread occupation of the Palestinian lands.