How did you find these photographs and documents?

I found them in my mother’s apartment in January of 2013. I was helping her move furniture and sort her belongings. If I hadn’t been there, they almost certainly would have ended up in the trash. She thought there was only one letter at first. But inside it, there was also a Christmas card with an envelope and four photographs, one of which was taken by a professional photographer.

Were you able to determine what you had discovered, that they were important historical documents?

My mother had told me about them – although just the one letter at first – and who wrote them: Hermine Braunsteiner. I had vague knowledge from a few years prior from my mother about a friend of the family who is supposed to have been notorious in and apart from her work in concentration camps in the Third Reich.

How did you proceed to research these documents?

I first spent a few weeks asking my mother about everything that she knew and could remember. After all, she had met Hermine Braunsteiner a few times as a girl and young woman.

Of course, I also looked at all of the online resources regarding the documents I could find at the time. The Reader by Bernhard Schlink is a famous book and it was obvious that Braunsteiner was a sort of template for the main protagonist, but I didn’t know that. I hadn’t heard of the book at that point. The first publication I contacted that showed immediate interest was the Austrian news magazine, which has high circulation. After an interview with a journalist in my mother’s apartment, he left me copies of all of the witness statements from different criminal proceedings against Braunsteiner that he had collected from the Simon Wiesenthal Archive in Vienna. Then I was contacted by an historian who had published a book on concentration camp guards in the Third Reich that included Braunsteiner. The more I dealt with Braunsteiner, the more I came to know. Just a few days ago (late April of 2015), someone else contacted me: a doctoral candidate from Salzburg asking for help with her research.

Can you tell us about Hermine Braunsteiner’s Background?

Hermine Braunsteiner grew up in a poor family living on the outskirts of Vienna. The street where her house stood, and likely still stands today, is on a hill leading to the Vienna Woods. Braunsteiner’s father was a butcher. In Vienna, she had a job in a brewery without good financial prospects, which is one reason that she went to England where she helped to keep a house, before finally going to work at the Heinkel Aircraft Works outside Berlin.

How did she become involved with National Socialism?

Through her landlord during her time at the ernst Heinkel Aircraft Works, who was a police officer and Nazi. Better pay and working conditions are also supposed to have been incentives for her to start working at the nearby Ravensbrück concentration camp.

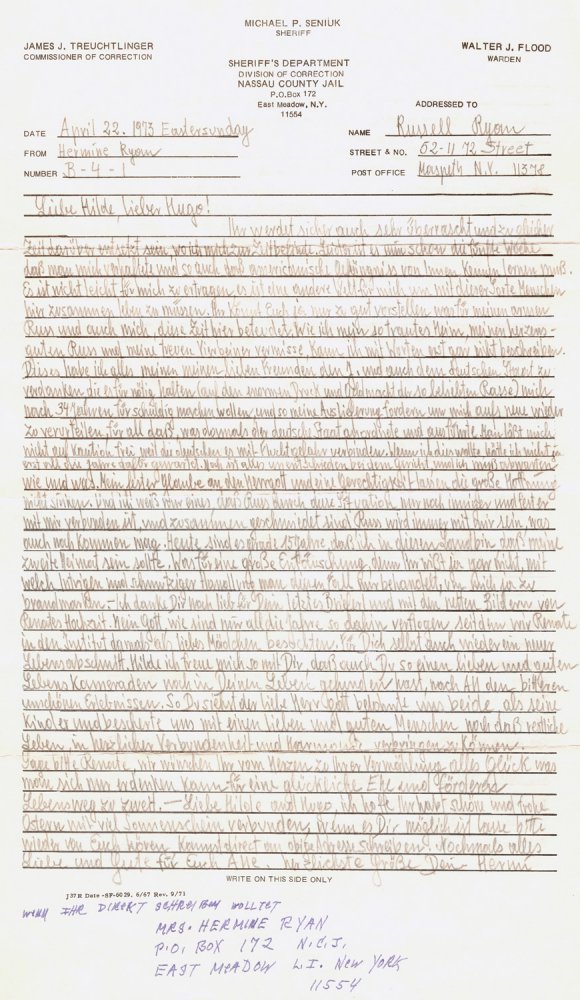

Letter written by Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan at the Nassau County Jail, USA, 1973 — Transcription

Describe Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan’s career in the Nazi system.

She was an overseer at Ravensbrück concentration camp from August 15, 1939 and she became the director of clothing storage in 1941. In 1942, she transferred to Majdanek, a concentration and death camp in Poland. She began to work there on October 16, and later became second in command, and the replacement for the Head Guard, Else Ehrich. In 1944, she was transferred back to Ravensbrück, where she was first made Director at the neighboring Genthin camp and finally Head Guard at Ravensbrück, the main camp.

She played an notable role in the concentration and death camp Majdanek. Do you see a connection between her position and her sadism?

She had different jobs and held different positions during her time there, from working in the clothing storage room up to being second in command and a replacement for the Head Guard. Like many other violent criminals in the Third Reich, she was not necessarily known among her peers – as far as records can attest – for physical abuse, neither before nor after. The context of the environment in which she found herself seems to have shaped and adapted her behavior.

Her sadistic nature seems to have fully developed at Majdanek. Whereas she “only” abused prisoners at Ravensbrück, she began to kill at Majdanek: men, women, and children; needlessly and arbitrarily.

During one selection, she heard whimpering coming from a man’s backpack after she struck him with a whip (she always carried a whip). She ordered him to open the backpack. Then she pulled out a bleeding child. Here, sources tell different stories – it is unclear whether she killed it right away or threw it on a wagon headed for the gas chamber.

She seems to have had a particular loathing for women and children (“They’re like shit”: a statement she made during the Majdanek trials). She was infertile, which was undoubtedly a factor in her hate. In this context, it is interesting that she refers to my mother as a “darling little girl” in the letter from her imprisonment prior to her extradition. Which is actually unbelievable. She and her husband also picked up my mother from her boarding school in Graz without informing anyone – she took her to eat schnitzel at the luxurious Weitzer Hotel. For my mother, Hermine Braunsteiner was Aunt Hermi. I spent a lot of time with my grandparents and, strangely, I remember hearing my grandmother say the name “Hermi” – her pronunciation was unique – without knowing who she was talking about. I can’t say for sure whether she meant Hermi Braunsteiner. But it seems natural that the family would have talked about her.

The prisoners of Majdanek gave her the nickname Kobyła.

Because the authorities in the camps didn’t wear name tags, they were inevitably given nicknames by the prisoners; clearly these people had to be named somehow to indicate their peculiarities and dangerousness. Braunsteiner was called ›Kobyła‹ at Majdanek, which in Polish simply means “mare”. She was called the Mare because, when she didn’t hit prisoners with her hands, she kicked them with her boots or trampled them to death.

Her abuses, which were often lethal, took many forms. From the extremely brutal selection of children, whom she grabbed by the hair and tossed onto the waiting wagons, to lashes with the whip. At Majdanek she often had a German Shepherd with her that she would let loose on prisoners.

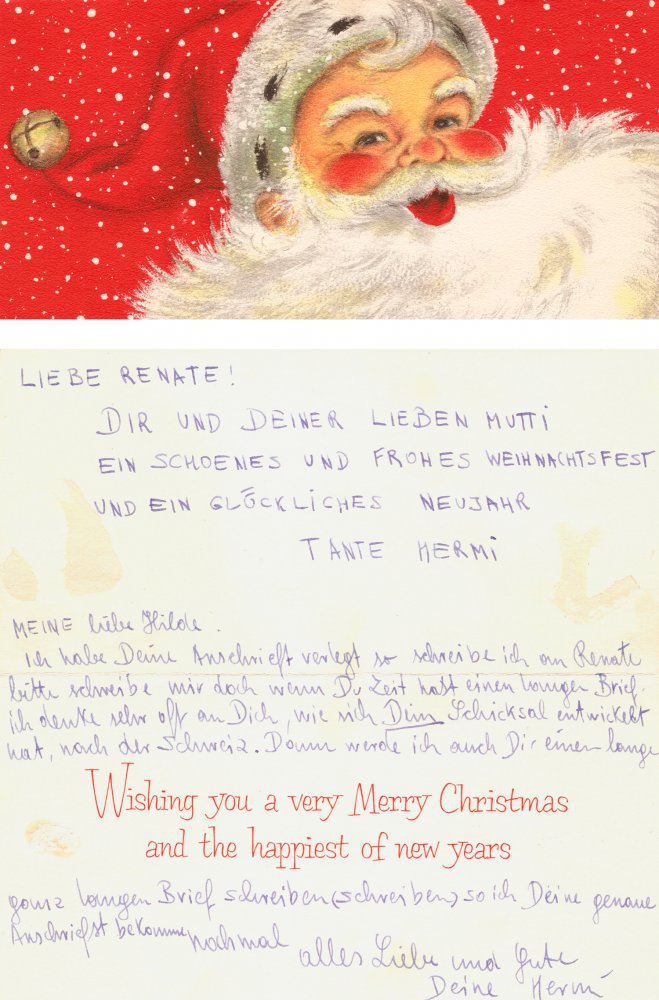

A Christmas card adressed to Hildegard and Renate Bex, 1959 — Transcription

Was she prosecuted for her crimes after the war?

She was imprisoned from May 6, 1946 to April 18, 1947 and then from April 7, 1948 to November 22, 1949. On the day of her release, she was sentenced by the People’s Court of Vienna to three years of imprisonment with hard labor, and her estate was seized. The grounds for this were “the crimes of torture and abuse as well as the violation of human dignity”.

In 1964, after immigrating to the U.S., she was found by Simon Wiesenthal and imprisoned again nine years later. She wrote the letter to my grandparents on the first or second day of her imprisonment.

How did the relationship between your grandmother and Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan come about?

They met while working as maids at different hotels in Kärnten, probably on the way to use one of the only ironing machines in the Villach area. The laundry would be brought there in hand wagons. My mother usually went with my grandmother to take it. We don’t know whether she met Braunsteiner there or on a group excursion to swim in Wörther Lake.

Did your grandmother know about Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan’s Past?

As far as I know, she didn’t. Supposedly, when she read the letter from prison, she shook her head and said, “This is inhumane”.

Tell us more about the Photograph from the Eibsee 1957.

On the back, Braunsteiner wrote, “From a lovely vacation at the foot of the Zugspitze on Lake Eibsee”. It’s likely that she had met her future husband Russell Ryan in Kärnten not long before (in a seed shop, we believe) and was vacationing there with him. The lion cubs were probably brought there by the photographer as a small attraction to get tourists to buy photos. The leather glove that Braunsteiner is wearing in the picture is very conspicuous and peculiar.

Did the U.S. authorities know about the Mare of Majdanek?

No, because she didn’t admit to having ever been convicted of a felony when she entered the country.

And Hildegard Bex in Lugano, Switzerland, 1962

Describe the context of the images from Lugano in 1962.

At that time, my grandmother had worked for several years in Switzerland as a maid in a hotel. Braunsteiner must have visited her there during a vacation. Who knows whether she found my grandmother in Austria or Germany. I doubt it, because at that time they were searching feverishly for Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann. The latter was executed in Israel in late May of 1962.

How was Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan discovered?

It was because of Simon Wiesenthal and a chance meeting with Majdanek survivors in a cafe in Israel in 1964. The women moved Wiesenthal to find the Mare. You can read about it in his book JUSTICE, NOT VENGEANCE: RECOLLECTIONS.

Ten years after she was granted U.S. citizen- ship, she was imprisoned in preparation for her extradition. Under pressure from the press and the extradition proceedings, she gave up this citizenship retroactively ad became a stateless person. She was very afraid of being extradited to Poland. From 1975 to 1981 her fate and the fates of others were decided in the Majdanek trials, the longest and most expensive trials in Germany at the time.

What reaction followed her discovery?

One NEW YORK TIMES reporter followed Wiesenthal’s trail and finally found her in Queens. This led to a front page article. Neighbors became incensed, and protests began to take place in front of Braunsteiner’s home. There was a bomb attack, but at the wrong house.

The newspaper articles in Austria were short and concise. It’s hard to determine how much attention the case received in her home country at the time.

How did your grandmothers react once she heard about Braunsteiner’s past?

We simply don’t know. My mother doesn’t remember anything and my grandmother has passed away. But because there was still contact until 1973, so for nine additional years, I would say that there weren’t any extremely negative effects. Unfortunately, only fragments of their postal communication have survived.

Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan wrote a letter from Nassau County Jail to your grandmother after her arrest. What can you tell us about that?

She was arrested on Holy Saturday in 1973. The very next day, she wrote the letter to my parents. How she dealt with it was much like her statements in reaction to her charges before and after. Self-righteousness, rejection of any culpability of the Nazi State – whose orders she claimed only to have been carrying out – and her undisguised hatred of Jews that is not only apparent in the letter, but that she also expressed previously in at least one newspaper interview. There, she said: “But they won’t leave things alone until they can harass and destroy everyone that had anything to do with the Nazi regime. Who do I mean by they? Who do you think – the Jews!” (Sie werden uns nicht ruhen lassen bis jeder und alles zerstört ist, was mit dem NS-Regime zu tun hatte. Wen ich wohl meine? Wen denken sie denn– Die Juden!).

With dog in New York, USA, 1967

How did Mrs. Braunsteiner-Ryan get extradited?

On August 22, 1968 the American lawyer Joseph P. Hoey called for Braunsteiner’s extradition after studying her case for four years. Almost exactly five years later, on August 6, 1973, she was finally flown back to Germany.

Which verdict and sentence were reached during the trial?

She was the only defendant to be sentenced to life in prison. However, this was only based on three of the nine charges, as much simply could no longer be proven without a doubt.

She was convicted of the following: Selection and murder of 80 people, aiding in the murder of 102 people, and selection and aiding in the murder of 1,000 people.

Describe the years leading up to Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan’s death.

She was pardoned in 1996 by the Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia at the time, Johannes Rau, due to her poor health. She was in a wheelchair because her leg had been amputated due to diabetes. She spent her last years in Bochum with her husband in a sort of pensioners’ home consisting of an assisted living facility, a hospital, and a retirement home. There, she had a 65 square meter two bedroom apartment and a volunteer caregiver.

One of her neighbors started a petition to have Ryan thrown out. Three others signed in addition to him. Braunsteiner died in 1999, just a few months after my grandmother.

Transcriptions

Letter written by Hermine Braunsteiner-Ryan at the Nassau County Jail, USA, 1973

Dear Hilde, Dear Hugo!

You will definitely be very surprised and at the same time upset to know where I am right now. Unfortunately it is now the fifth week I was arrested and so also get to know the American prison from the inside. It is not easy for me to bear, it is another world for me to have to live here together with these kinds of people. Of course you can imagine what this time here means for my poor Russ and also for me. I cannot put into words how I miss my familiar home, my good-hearted Russ, and my loyal four-legged friends. For all of this I have to thank my my dear friend J. And also the German government who see fit (under the enormous pressure and financial power of the most esteemed race) to judge me guilty after 34 years, and so to demand my extradition to convict me again, for everything that the German government designed and carried out back then. They will not let me out on bail because the Germans think I might run. If I wanted to, I wouldn’t have waited all these years to do it. The court hasn’t made a decision yet, and I have to wait to find out what and how. My firm faith in the Lord our God and a justice do not allow my great hope to fade. And I just know one thing, that this situation only makes Russ even more deeply and tightly bound to me, and are welded together, Russ will always be with me, whatever may happen. Today it has been 15 years that I have been in this country that is supposed to be my second home. What a huge disappointment, because you don’t even know what intrigue and dirty dealing has gone on in their treatment of my case, just to denounce me. Thank you a lot for your last letter and the lovely pictures of Renate‘s wedding. My God, where have all the years gone since the time we visited Renate at the institute as a darling little girl. That was a new part of life for you too. Hilde I am so happy with you, that you also managed to find such a good and kind partner for your life, after all the bitter ugly experiences. As you see the Lord our God rewarded us both, as his children and blessed the rest of our lives with a kind and good person, to be able to bring us together in honest communion and harmony. Please tell Renate that we wish her all the good that anyone could imagine from the bottom of our heart for a happy marriage and the rest of their paths together. – Dear Hilde and Hugo, I hope that you have nice and happy Easter with lots of sunshine, if you can let me hear from you again please. You can just write back to the address at the top. Best wishes to you all again.

Warm regards, your Hermi

Christmas card adressed to Hildegard and Renate Bex, 1959

Dear Renate!

Merry Christmas and a happy New Year to you and your lovely mama.

Aunt Hermi

—

Dear Hilde.

I lost your address so I’m writing to Renate. Please write me a long letter when you have time. I think of you often, where your life has led you, to Switzerland. Then I will write (write) you a long, very long letter as I get your exact address. Best wishes again.

Yours, Hermi