Over the past few years the use of user generated content to investigate conflict zones from afar has been on the rise. Journalists, human rights organisations, governments and more have become increasingly interested in the use of content from conflict zones, be it from social media accounts or more unusual sources. In my own work I have identified weapons smuggled to Syrian rebels, investigated chemical attacks in Syria, tracked the missile launcher linked to the downing of MH17 in Ukraine, and much more.

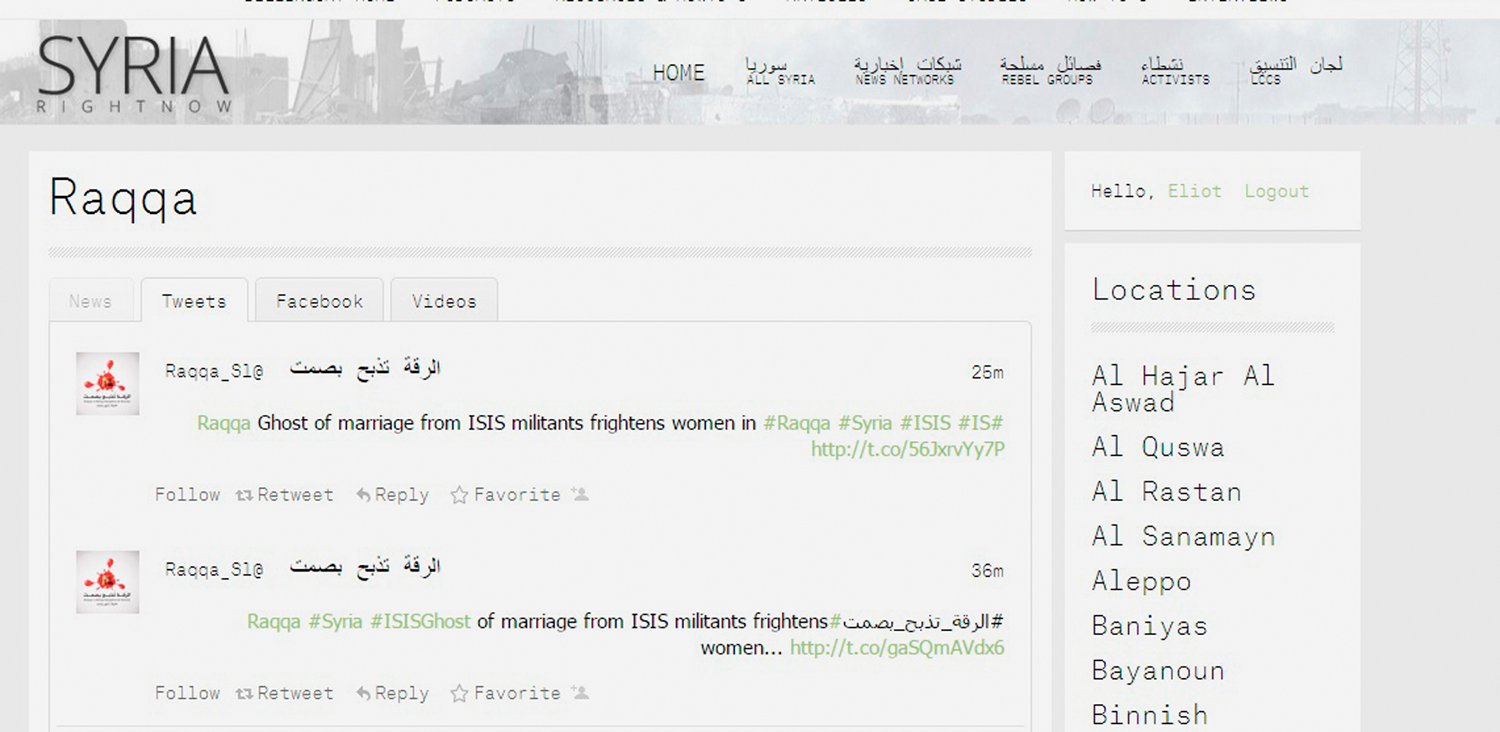

Syria Right Now zeigt Social-Media-Posts aus Raqqa, Syrien.

Each stage of working with user generated content doesn’t exist and a vacuum, so it’s important to understand each stage of the process, and what those stages are. To begin with, the content is created, be it activists filming a protest a professional photographer in a war zone, or any number of potential sources. Understanding the thought process behind the contents creation is important, as is how that’s then shared. In the case of Syria you have an organised structure of social media accounts that has grown organically during the content due to limits on internet access, so videos from opposition groups are shared on accounts they use frequently. This means when you see what’s claimed to be a Syrian opposition video posted to a brand new account you should immediately question the authenticity of the video.

A well-known example of this is the “Syrian Hero Boy” video, which turned out to be fake, and was originally posted on a brand new YouTube channel. In the case of a conflict like Ukraine things are somewhat trickier. Internet access is relatively unrestricted, meaning that despite their being pages for various groups in Ukraine, there’s also masses of content posted by citizens living in both Russia and Ukraine to their private social media accounts. Keyword searches on social media platforms can bring up a lot of useful content, but also a greater volume of irrelevant content. Content unfiltered through activists or armed groups allows investigators to find more hidden gems, but also results in a more time consuming investigation process.

Standbild aus ›Syrian Hero Boy‹

When considering all these stages it’s useful to have a variety of tools and techniques that can be used and deployed at each stage. Having a toolbox is far more useful than a Swiss Army Knife when working with user generated content. With geolocation many people are aware of sites like Google Maps, but are unaware of Yandex Maps, with its own version of Google’s Street View that covers sites in Ukraine and Russia not covered elsewhere, hugely useful in the current conflict. It’s worth keeping an eye on new tools that are being created, or discovering ones that already exists, and reading the work of other people investigating user generated content for ideas and inspiration for your own work.

1. Discover

After the creation and sharing of the content, there’s then the discovery stage. It’s one thing to share the content, quite another for anyone to actually find it. In the case of Syria because of the way Syrian opposition social media channels are organised there’s actually only a relatively small number (a few thousand) compared to regions where internet access is unlimited. This means it’s possible to create a subscription list to all the YouTube channels used by the opposition, or follow all their Twitter and Facebook accounts, and have a steady stream of content. More advanced platforms, such as Syria Right Now are being developed that make this process even easier, even for someone who is new to the conflict.

Standbild eines Videos, dass einen Buk Raketenwerfer zeigt, 17. Juli, Snizhne, Ukraine

In the case of a conflict like Ukraine things are somewhat trickier. Internet access is relatively unrestricted, meaning that despite their being pages for various groups in Ukraine, there’s also masses of content posted by citizens living in both Russia and Ukraine to their private social media accounts. Keyword searches on social media platforms can bring up a lot of useful content, but also a greater volume of irrelevant content. Content unfiltered through activists or armed groups allows investigators to find more hidden gems, but also results in a more time consuming investigation process.

2. Preserve

Next we have to look at preserving content. This step is frequently overlooked, but with content being frequently deleted from a variety of reasons it’s wise to make some sort of backup or archived copy of content. Videos can be downloaded using a variety of tools, including sites like Keepvid and Clip Converter, and Archive.org allows anyone to select pages to be archived. In the case of the downing of MH17 in Ukraine on July 17th one video showing the Buk missile launcher linked to the downing of MH17 was quickly deleted, and if it wasn’t for people immediately downloading the video it would have been lost, so it’s important to quickly make copies of important content as it can vanish as rapidly as it first appeared. As part of this, organising content is also useful. In my work on Syria I’ve created multiple YouTube playlists for different videos, be they for specific events or tracking a type of weapon.

3. Verify

Next there’s the matter of verification. Geolocating content has become well known, but there’s other way to collect more information on content. What’s useful about understanding the way in which content is shared online is that we also learn where we could find additional content. With Syria, we know Syrian opposition groups generally have YouTube accounts, Facebook pages, and Twitter accounts, so if we find content on one platform it’s possible to find additional content on their other social media accounts. With Ukraine, if there’s an incident filmed in a town it’s worth searching social media for accounts that might be related to the area the incident took place in.

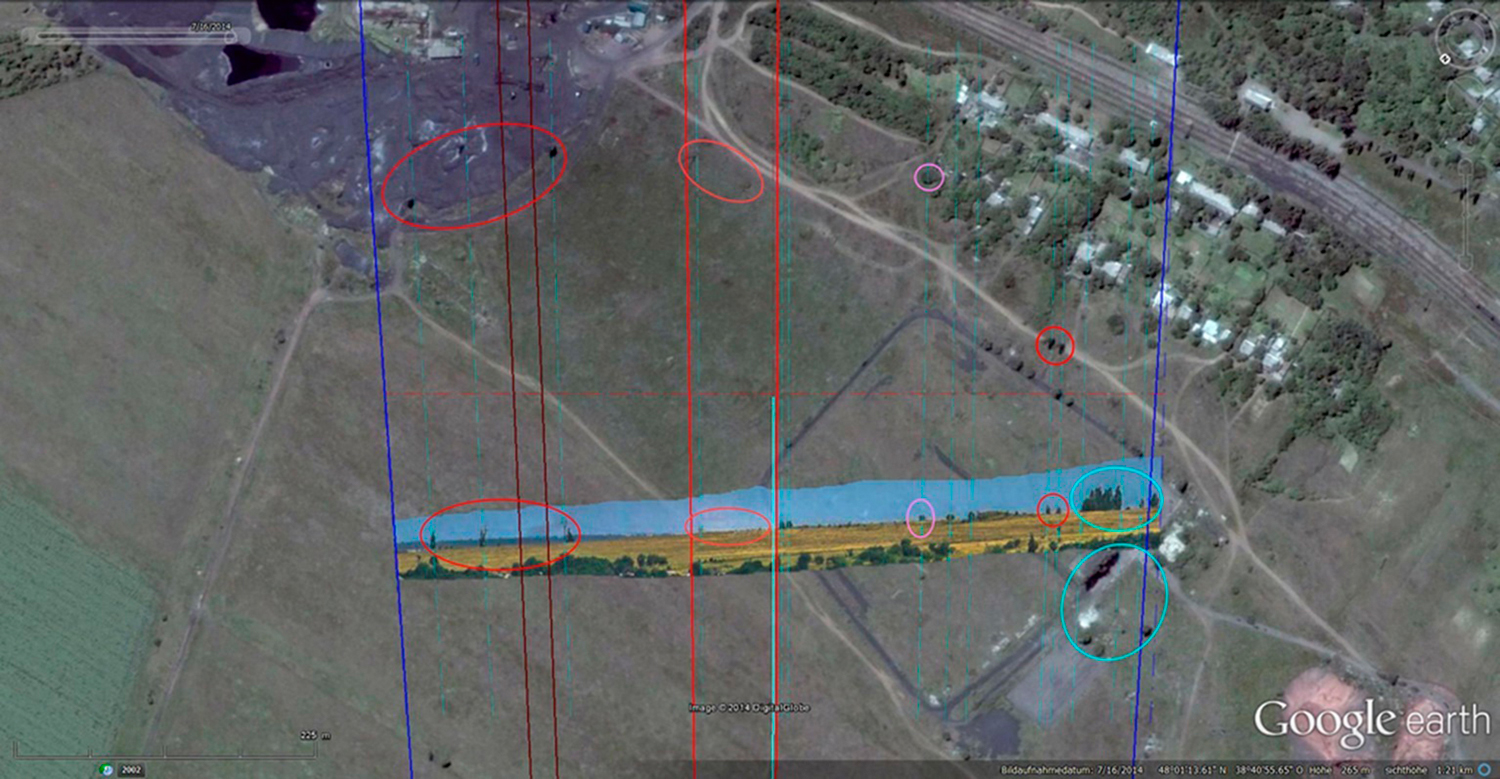

Ortsbestimmung eines Fotos im Zusammenhang mit dem Absturz der MH17

4. Publish

Once the content is verified we can publish the content. It’s not always a matter of writing an article or piece of analysis, in the case of Bellingcat Ukraine Vehicle Tracing Project we’ve been collecting reports of Russian military vehicles inside Ukraine, geolocating the videos, then adding them to a database which is linked to the Silk Platform to produce various embeddable visualisations of that data. This means that anyone can create visualisations based on that data, customised to their needs, allowing it to be used beyond the ways we’ve devised.

5. Get Started

But if you’re new to all of this, where can you start? At the very least any one working with user generated content should be learning about the most basic verification tools. After that, basic geolocating skills are also easily acquired. There are many case studies and further how to guides on the Bellingcat website.